Anglo-Saxon Romsey

The Evidence in the Landscape

Anglo-Saxon Land Use

A Very Large Jigsaw Puzzle

Attempting to understand the development of Romsey during the Anglo-Saxon period involves piecing together the evidence from a variety of sources. In a study based on landscape analysis the information can be added to a map, combining topography and geology, historical maps and charter landmarks. Viewing Romsey within the wider landscape helps to explain how the settlement supported itself and how it fitted into Saxon Wessex.

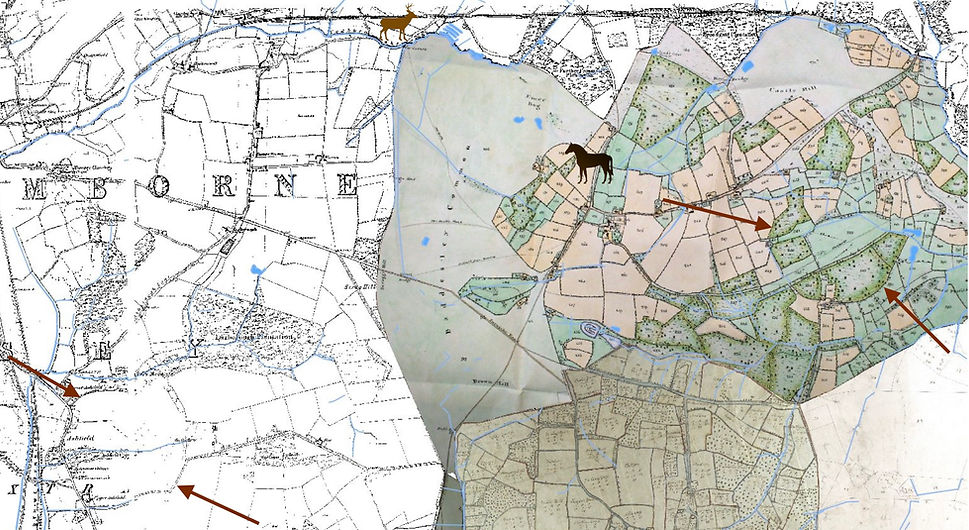

LiDAR base map with surface water. A detail of the 1845 tithe map shows the location of the town. Symbols represent land use: arable on the river terrace; the cattle enclosure at Ashfield; a horse stud at North Baddesley; a deer park at Ampfield; and the site of a signalling beacon on Toot Hill. Two additional red arrows point to a military road, Stemn’s path that provided access to the ‘lookout’ hill.

LiDAR provides a useful background for building up a picture of land use. It is particularly relevant for a study of Saxon Romsey. Here the topography was an important factor in the choice of a site for the early religious community, on a river terrace overlooking the floodplain. This lowest terrace shows up clearly in the LiDAR, with a highlight at its western edge and earlier terraces rising to a plateau to the east. The brickearth topping the terrace provided an easily-worked, well-drained and fertile soil, ideal for arable farming. The terrace south of the town has never been built on. Field banks show up in the LiDAR alongside the old road heading south towards Southampton.

Cattle were essential to a farming economy. Oxen pulled the ploughs to grow the crops and the carts to carry it from the fields. Evidence for stock raising is visible in the landscape. ‘Oval’ enclosures were probably used mainly for over-wintering the breeding herd and plough oxen. They are often associated with a nearby area of stream-side pasture suitable for cows and their calves and used for dairying. The place-name wic seems to refer to this seasonal activity. An enclosure at Ashfield, south of Romsey, can be seen on the 1787 map of the Broadlands Estate and the 1845 tithe map. The North Baddesley estate map of 1826 shows a less well defined enclosure of a similar size.

Detail of the 1787 Broadlands Estate map centred on the Ashfield oval enclosure. A curved perimeter efficiently enclosed a maximum area with the minimum length of stock-proof boundary. The drawing was aligned to fit the sheet of paper, rotated 29 degrees clockwise from north.

The Ashfield enclosure on the 1845 Romsey tithe map, on LiDAR base map. The small stream running through the centre would have supplied drinking water for the cattle during the wetter winter months.

Arrows point to the Ashfield oval to the left of the map. Curved boundaries on the 1826 North Baddesley estate map appear to define another enclosure of a similar size. This probable enclosure was identified while working with North Baddesley local historian Jane Powell on the solution of the North Stoneham charter. The cattle enclosures are likely to be early features in the landscape. A cattle bone from an excavation in Romsey has been radiocarbon dated to the 7th century.

Google Maps/Google Earth view of the changing landscape south of Romsey. A new housing development is underway on the western edge of North Baddesley, along Hoe Lane. Planning approval was granted in January, 2025 for the building of houses on the site of the tyre dump within the Ashfield stock enclosure.

A road labelled Dirty Drove, left arrow, heads towards the enclosure from the west. Another roads heads north to Zion Hill Farm on the southern edge of the semicircular enclosure boundary

North Stoneham shares a boundary with Chilworth, shown here on the 1755 estate map. The arrow points to a section of the boundary described in the charter of 932. The boundary circuit was heading north at this point on Byrewege, on Byre Way. The word byre meant the same thing in Old English as it does now, a cowshed or cattle shelter. The North Stoneham boundary turned east when it reached Cytanbroces aelwilme, the spring of Kites Brook, a name that survived as Kites Oak Copse on the North Baddesley estate map. Presumably the Byre Way continued north to the cattle enclosure.

The Anglo-Saxons didn’t use horses as draught animals - oxen served in that role - but they would have used packhorses to carry goods. Horses would have been able to manage rough terrain unsuitable for carts or wagons. One of the landmarks on the Michelmersh charter of 985 was the horseweges heale, the corner of the horse way. At this point the boundary meets the road heading towards Farley, a steep uphill climb. The name suggests it was suitable only for horse transport. The horse on the maps above shows the location of stodleage, stud lea, on the 909 Chilcomb charter. Horses raised at the stud could have grazed the wood pasture - the lea - or on the adjacent grassland, now Baddesley Common.

A compilation of historical maps superimposed on LiDAR hillshade. Left - 1845 Romsey tithe map showing land use. Lower centre - 1755 Chilworth estate map. Centre right - 1826 Baddesley estate map. Top right corner and centre top - outline version of 1588 Hursley estate map, redrawn by Roger Harris. The estates surround Baddesley Common in the centre of the image.

Pasture would have been an essential resource for raising livestock. The Chilcomb charter of 909 proceeds from stud lea to ticnes felda and the Ampfield charter, written sometime between 909 and 924, starts and ends at ticcenesfelda wicum, on the southern edge of the deer park. A feld was an area of open land - Ticcenesfeld must have been the name for, at least part of, Baddesley Common. The wording of the Chilcomb charter doesn’t define the line of the boundary as it crossed the feld. An open, unfenced grassland could have been shared by the surrounding estates through an allocation of grazing rights for a specified number of animals.

3D map showing the land described in the Ticcenesfeld/Ampfield charter. The Bishop’s Bank forms the western boundary. The green arrow points to the probable location of the holding stow. Most of the land is on a bedrock geology of London Clay and would have been largely woodland in the 10th century, as it was when the 19th century OS map was drawn.

A charter granting land at Crawley by Edward the Elder to Winchester Cathedral included the bounds of an additional piece of land at Ampfield. The boundary description starts by heading north from Ticcenesfelda wicum along a haga, the Bishop’s Bank, and returns to the start along a haga. The enclosure of at least part of the area by a haga, a bank topped by a hedge or fence, suggests that this was a deer park. The holding stow was a landmark on the eastern boundary. Stow means place and a hold was a corpse. A ‘corpsing place’ makes sense in the context of a deer park - the location where the deer carcasses were processed following a hunt.

Detail of the 1588 estate map by Ralph Treswell showing a deer park at Hursley. North is to the right. Ampfield was part of the Hursley estate. Like its Saxon predecessor, the deer park on the 16th century map is wooded and crossed by a stream. The deer are contained within the park paling, a fence built along the top of a bank. The boundary bank, with its inner ditch, has survived for much of its length. Sections are scheduled by Historic England.

The deer park on a copy of Ralph Treswell’s 1588 map of the Hursley estate, with modern surface water, viewed in 3D. The park pale runs along the edge of a drove road at the southern end of the deer park, suggesting that the road predates the park which was created in the 12th century. The drove road with its characteristic funnel opens on to the grazing land of Ampfield and Baddesley Commons, lower left.

The outline version of the 1588 Hursley estate map with surface water and modern roads added. The A3090 is shown in red, running along the Straight Mile to Ampfield then east and north around the medieval deer park of Merdon Castle and through the village of Hursley.

Plan of Merdon Castle and Hursley Park by OGS Crawford, Archaeology in the Field, p195. The banks are visible on the 1588 Hursley estate map.

The park pale on an outline version of the 1588 Hursley estate map overlaid on a 3D LiDAR hillshade image.

This composite 3D LiDAR image shows features surviving under Ampfield Wood. The height has been exaggerated - the hills are less steep than they appear. The curving pale of the Hursley deer park is on the right. The Portland Bank, which OGS Crawford traced on the ground, is visible for most of its length. The ridge of high ground at the centre is cut by traffic ruts, some continuing through the pale and into the park. The 1588 Treswell map shows a gate near the location of the tracks heading east off the ridge; tracks leaving the ridge to the north appear to pass under the pale. It is unlikely that these tracks, created as people and livestock shifted paths to avoid obstructions and muddy puddles, would have developed in woodland. The landscape must have been more open at the time they formed.

The Hursley deer park and outer enclosure mapped with LiDAR hillshade and modern surface water. The outline drawing is somewhat out of alignment with the features on the ground. The curved line at the southeast corner of the outer park bounded the trackway visible in the LiDAR on its west and north sides.

This copy of the 1588 Treswell map, drawn by Roger Harris, shows a road leading to a gate in the Portland Bank. The LiDAR trackway follows the curved line to another gate through the park pale.

The 1588 map shows the funnelled entrances to the roads leading from Anvile (Ampfield) Common. The funnels aided the movement of livestock from the grazing land.

The boundary of the Out Park enclosure, yellow arrows, is visible in the LiDAR for most of its length, extending from a well preserved section of the Park Pale, white arrows. A trackway, marked in green, crosses the pale and runs towards Hawker’s (Hauckers) Hill. It follows a straight course over difficult terrain. The sloping ground has been cut back and levelled and the gullies draining the higher ground have been bridged to carry the track.

The straight trackway with Hawker’s Hill on the left. The section of the track west of the park pale measures 550m.

Profile of the line taken by the straight track.

The straight trackway appears on the first edition OS map, surveyed in the mid-19th century, heading west across Hursley Park from Southampton Lodge and into Ampfield Wood. It survives as a public footpath.

The western side of Hawker’s Hill appears to have been extensively quarried. A series of shallow pits extend along the side of the hill north of the Portland Bank for a distance of 115m, brown line. Further pits and scoops lower down the slope can be seen in a side-on view of the hill. The geology here is the Whitecliff Sand Member (see the Geology page) which includes deposits of clay as well as sand. Large pits at the southern end of the hill are clay diggings. The date of the straight trackway is unknown. Was it built as an access road to the quarry? Could it be Roman?

The LiDAR hillshade image shows Merdon Castle at the northern end of a chalk spur within the deer park. The motte and bailey castle was built in the 1130s on the site of a Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age hill fort. The rectangular field banks laid out along the ridge and the lynchets on the east side predate the castle and deer park and are probably contemporary with the hill fort. Lynchets are terraces formed by ploughing sloping ground.

A 3D LiDAR view of the lynchets east of Merdon Castle. The village of South Lynch is in the valley below Violet Hill, top right.

Adding contour lines to the map shows the slope of the chalk ridge, affording Merdon Castle a distant view to the south.

A view looking south from Merdon Castle drawn by GF Sargent in 1830. The house within the deer park on the 1588 Treswell map was behind the mansion in the picture.

A view of the deer park, complete with a herd of deer, published in 1839. Hursley Park is now owned by IBM.

3D LiDAR hillshade image of the landscape surrounding Hursley Park. Chalk bedrock creates a distinctive landscape, dissected by dry valleys and pock-marked by chalk pits. The geology changes in the lower part of the image where streams flow through the clays, sands and silts at the edge of the Hampshire Basin. The height has been exaggerated to bring the minor, man-made features into view. These include, to the north, a Roman road near an 18th century monument on a mound and several barrows. The outlines of early field banks and the lynchets on the sides of valleys represent the labour of many generations of farmers in what was a heavily utilised landscape.

The Roman road between Winchester and Old Sarum cuts across the landscape. Quarry pits are visible in the LiDAR alongside the road. South of the road at the centre of the image is a Bronze Age bowl barrow. This is likely to have served as the focal point of the Saxon execution site recorded as a boundary landmark in the Chilcomb charter of 909 (see the Charters page). The barrow is a scheduled monument.

Second edition OS map showing the Winchester-Old Sarum Roman road north of the Farley Mount Monument. The Tumulus (barrow) on the right was used as boundary landmark; it appears on the 1588 Treswell map at the northwest corner of the Hursley estate, labelled 'Robin hudes butt'.

Looking north from the west boundary of the Hursley Estate, the Farley Mount Obelisk appears as a white dot on the horizon. The stone obelisk was built on top of an earlier earthwork; a mound made up from the chalk bedrock would also have been visible as a white landmark on the crest of the ridge.

The long-distance view from Farley Mount on Beacon Hill. An Armada beacon was sited on the hill, and it was probably also part of an Anglo-Saxon beacon chain (see the Defence page). The obelisk was built in the 18th century to commemorate a horse named Beware Chalk Pit.

Most of the small fields mapped by Ralph Treswell in 1588 have disappeared from the landscape. The houses and fields of the small hamlet of Marden have been replaced by Merdon Farm.

Read more:

Where Was Ticcenesfelda Wicum?

Further Thoughts on Ticcenesfelda Wicum

An ‘Oval Enclosure’ at Ashfield - Cattle in the Anglo-Saxon Landscape

Further Reading:

Andrew Margetts The Wandering Herd: The Medieval Cattle Economy of South East England c. 450-1450. Windgather Press, 2021.

OGS Crawford Archaeology in the Field, 1953.